Can a person be inherently evil? | Premier Christianity Magazine

Dr Matthew Knell

LST’s Dr Matt Knell, lecturer in Historical Theology and Church History, writes for Premier Christianity Magazine about the cases of serial killers such as Lucy Letby, which raise hard questions about the nature of evil. There may be no neat answer, says Matt, but biblical principles can provide some guidance.

This article was originally published in Premier Chrisitanity Magazine and has been republished with permission.

The starting point for discussions such as these is always the fallenness of humanity. “For all have sinned and fall short of the glory of God” says Romans 3:23. Paul then goes on to say that our very nature is to be “slaves to sin”. This is an important biblical principle: being comes before action. What we are leads to what we do. Think of Jesus talking about good and bad trees and the fruit they produce in Matthew 7:17-23.

This does not need to lead us into discussions of Augustine or doctrines of original sin. It merely points to the consistent Church teaching that after our first parents, humanity needed salvation; that sin and its effects are, universally, part of our nature. Additionally, no aspect of a human person is separate from another – mind, body, spirit – so we should not limit what is affected by sin, nor the types of evil that can result from the corruption that exists.

A matrix of sin and grace

Recognising the complexity of sin in a person, it can be useful to talk about a ‘matrix’ of sin, and of grace. Some of the impact of sin on our lives comes down through generations – either through the brokenness of creation in general, or through the specific actions of individuals. Examples would be inherited traits that run in families, or the effects of drug abuse during pregnancy on a newborn baby.

Then there are the formative elements of a person’s character: family experience, culture, education and the values and beliefs that become instilled in them.

A person’s own actions (particularly their struggles with temptations, successful or not) affect their view of themselves, others and God. For many, the most important thread of sin in their ‘matrix’ is the sins committed against them by others, over which they have no control.

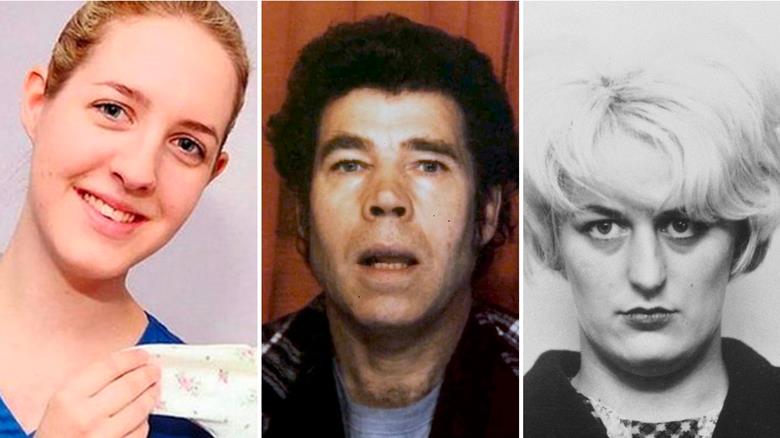

Image courtesy of Premier Christianity.

Finally, we must consider spiritual attack. The denial of the demonic is a dangerous route to take biblically, while an over-emphasis can likewise be extremely harmful. It may not be easy to accept, but I do believe there are demons at work in this world, and that their work is not simply confined to the spiritual realm. However, it seems to mostly be subtle, one element interplaying with others. Prayerful awareness of their existence seems the wisest course.

The result is a massively complex, individual engagement with sin that is different for everyone. Whether Christian or not, we are all tempted, and repeated sins can gain a hold on us. We are often blind to many of the effects of sin in our lives, while others we are consistently aware of.

All of this must be balanced by a matrix of grace. Grace works in the same dimensions as sin, restoring humanity through generations, allowing societies to identify elements of justice and mercy, inspiring individuals to love and encouragement, and, for Christians, transforming hearts and minds so that we become more Christ-like.

What do we do?

When considering something as shocking as the Lucy Letby case, Christians involved in the legal system have a duty to carry through justice, as far as their wisdom allows under the laws of the state. For the rest of us, I’d highlight three areas of action:

1. Prayer and support for victims. Where we are able, we should seek to bring grace into people’s lives, at a cost to ourselves if necessary. This is not only about immediate victims, but becoming more aware of the number and range of victims of sin around us. I have, sadly, had far too many conversations where it has become apparent that the person I’m talking to has suffered, often in ways that I couldn’t have known before, or in ways that they are unable to tell me. As the Church, we need to be far more aware of the brokenness in people’s lives and more willing to sit with them in that brokenness.

2. We must seek to help those who perpetrate, or who are tempted to perpetrate, acts of violence (or other sins) against others. God does not will that people sin, though he knows the sins that will be committed. Rather, God wants to empower his people to be instruments of grace. If we truly submitted all of our resources to him, there would be less suffering in the world today. People who commit acts of evil are corrupted in many ways, some of which they are aware of and others they are not; some of which they have genuine choice about and others that have developed a power over them.

Violence and abuse are rife in society and, unfortunately, within the Church, too. We need to protect the vulnerable, name sin and take action where harm is being caused; to foster accountability in light of our love for God, his name and his people. This is one area where Western individualism has been most destructive to the gospel and the Church.

3. We must recognise the threads of sin in our own lives – and the threads of grace that we can be thankful for – and understand where patterns of sin or temptation are gaining a hold over us or have become normalised. Churches must create safe spaces where these struggles can be shared and God’s gracious presence can be brought in.

Rather than focusing on the ‘bookends’ of the faith – entry through the cross and our exit into glory – the Church needs to recognise that we are called to minister primarily in the in-between, when we are not the people we are called to be, and when those we love are struggling with the effects of sin in their lives.